About the Author

An Interview with Solveig Eggerz

An Interview with Solveig Eggerz

Published by the Washington Independent Review of Books on July 21, 2020

You have said that you started your most recent novel, Sigga of Reykjavik, 25 years before it was published. What took so long?

At least 25 years ago, I began researching the history of Iceland, especially the 20th century. Every year, when I visited my parents in Iceland, I copied from books, newspaper articles, whatever I could find. I did interviews with people, especially those who remembered World War II. When I returned home to Alexandria, Virginia, I translated everything from Icelandic to English. I also collected a lot of materials from U.S. sources — for example, about the Battle of the North Atlantic, which took place in the ocean near Iceland. Soon, I had stacks of these historic materials. What to do with them? I wrote a couple of articles about Iceland’s role in World War II…[but] I didn’t want to write a history book. Why not write a novel?

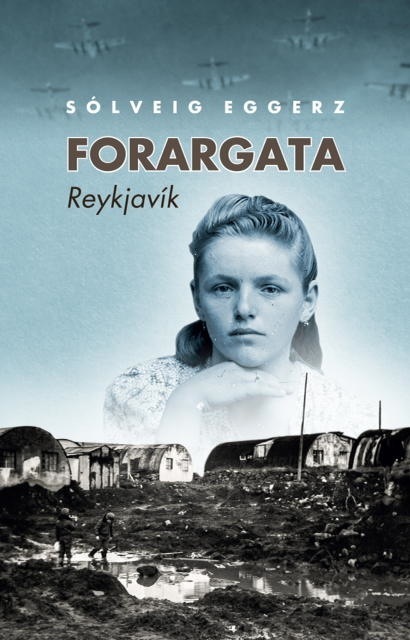

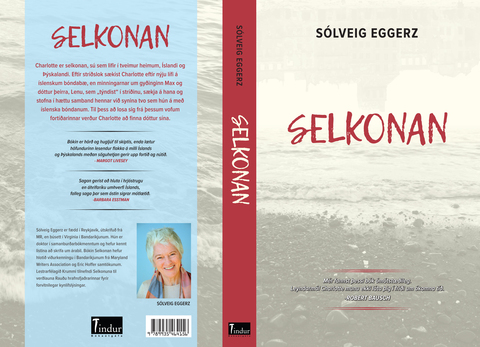

Since I’d never written a novel, I started taking workshops at the Writer’s Center in Bethesda. I did stacks of revisions, often inspired by my lively writers group. Over the years, I changed the protagonist from a German-Jewish male to an Icelandic female. When my writers group didn’t like the name Hervör, I changed it to Sigga. I took a break and published another novel, Seal Woman. Then I revised Sigga one last time. Finally, Sigga was translated into Icelandic and published in Iceland. Getting it published in the U.S. took some time. It all adds up to about 25 years — maybe longer! At that rate, long-lived writers might produce four books in a lifetime.

Both of your published novels — Sigga and Seal Woman — are set largely in Iceland, your native country, although you’ve lived in the United States for many years. What features of Iceland and its culture keep drawing you back creatively?

Even though I have only lived a total of six years in Iceland, I have always been afflicted with a yearning for the place my Icelandic parents called “home.” My father’s entire career was with the Icelandic Foreign Ministry, utanríkisþjónustan, in three different countries — [the] U.K., the U.S., and Germany — so I grew up in those countries. But the connection to the homeland was always there. Unlike the U.S. State Department’s system of “home leave,” the fledgling Republic of Icelandic could not afford to bring us home every two years. Our lives felt like exile. So we kept Iceland in our hearts and imaginations. The yearning was planted in me by my parents the minute we left Iceland for England, two years after my birth. And it flourished. Probably both books grew out of that yearning.

Your novels have been printed in both U.S. and Icelandic editions. Which language do you write in? And do you translate the books yourself?

Icelandic was my first language, but after spending 11 years of my childhood in England and the U.S., English became my “school language” and my language of expression. While I often think in Icelandic, English is for writing. No, I don’t translate the books myself. I wanted someone who is as strong in Icelandic as I am in English to create the Icelandic version. For me, a translation is a new creation. My cousin, Hólmfríður Gunnarsdóttir, offered to translate Seal Woman. Because she is an excellent writer herself with a strong sense of the nuances of Icelandic, her Icelandic version of Seal Woman, or Selkonan, may be a better book than the original. For Sigga of Reykjavik, I hired a translator. But I worked closely, word for word, with both translators.

Your novels have strong female protagonists, and two of Iceland’s last five prime ministers have been women. Does that culture provide greater scope for women’s development?

Sigga of Reykjavík is set during the first half of the 20th century in Iceland, when women’s work was not valued at the same level as men’s. Women might receive half the salary of men for similar work. This was certainly true in the fish industry where Sigga worked. On the docks, she dressed as a man to earn “a man’s wage” unloading coal from ships.

When I graduated from high school, Menntaskólinn í Reykjavík, in 1963, wage and opportunity inequities still prevailed. I am proud to say that my classmates from our all-girls class fought ferociously in the late sixties and early seventies to rectify the enormous gender gap. Those struggles laid the groundwork for today’s society, in which women are engaged in all the professions — from prime minister to surgeon general.

I believe also that the literary culture of Iceland, as expressed in the Icelandic Sagas, contributes to the development of strong-willed women. The outsized, sometimes imperious female characters in these medieval stories influenced my writing. They also crept into Sigga’s view of herself. During evening readings on the farm, Sigga learned to admire the determined and self-assured women of the sagas.

You are also a storyteller and lead storytelling workshops. How does that talent influence your writing?

Storytelling to an audience is demanding in a different way than writing a story. If audience members fall asleep or begin talking among themselves, the teller can surmise that the story isn’t as gripping as she thought it was. Telling a story is good discipline. It keeps one focused on the true components of story — character and conflict — rather than drifting into a flowery description of a balmy day. Storytelling also helps the writer develop the habit of mercilessly throwing adverbs and adjectives and other whatnots overboard.

Has the covid-19 lockdown influenced your writing in the last few months — either your enthusiasm for it, or the subjects you want to write about?

It has increased my enthusiasm but not changed the subjects. Covid-19 lockdown has its benefits. It has caused me to set a writing schedule and try to stick to it every day. Lockdown is a situation that invites a turn inward. I’m reading more, pondering ideas, and staying put. Like many writers, I’m an introvert anyway, so maybe the lockdown just escalates the natural instinct toward what I call interiority. With minimal social life, perhaps we live more in our imaginations. May I call the consequent mindset “enthusiastic introversion”?

What’s next?

I’ve been teaching memoir and personal stories both through the Writer’s Center in Bethesda, Maryland, and to incarcerated populations in Northern Virginia. Not having written my own story, I began to feel a bit of a fraud. One of my current projects is writing my own memoir. On the side — but memoir and novel keep switching places — I’m also writing a novel NOT set in Iceland. Yes, the protagonist is female. I’m hoping she’ll become a strong one.

David O. Stewart is a member of the Independent’s board of directors. His novel The Lincoln Deception was recently re-released.

Bio

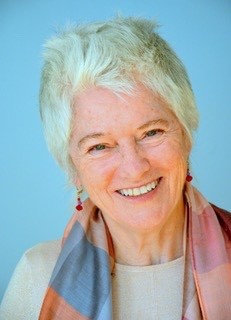

A storyteller, a teacher, and a writer, Solveig Eggerz has told folk and fairy tales in Alexandria, VA, schools, in DC’s homeless shelters, and in Northern Virginia’s detention centers.

Her writing students have ranged from firefighters at Reagan National Airport to Central Intelligence Agency staff, to civilian and military personnel at the Department of Defense. Currently she teaches personal stories and memoir at the Writer’s Center in Bethesda, MD and in Northern Virginia jails.

She has written for newspapers such as Roll Call, Alexandria Gazette-Packet, and The Washington Daily News. Her essays and stories have appeared in The Delmarva Review, Palo Alto Review, The Christian Century, Midstream: A Monthly Jewish Review, and The Northern Virginia Review.

Having grown up in four countries, she speaks three languages and struggles with Italian. In attaining her PhD from Catholic University in Comparative Literature, she focused on medieval anti-feminist satire.

Selkonan, Seal Woman in Icelandic, publisher Tindur, Akureyri, 2017

Available from https://www.penninn.is